The Seventieth Annual General Meeting will be held at Broomfield Parish Church and Hall, Church Green, Broomfield, Essex, CM1 7BD

Remembering our 2022 AGM

On a blowy autumn day, we remember a blowy summer day at Boxted. We were well looked after and thoroughly enjoyed our day at Boxted Airfield Musuem (www.boxted-airfield.com), especially meeting up with all our friends after a break of two years.

Photo courtesy of John Camp.

Notice of 2022 Annual General Meeting

The Sixty Ninth Annual General Meeting will be held at Boxted Airfield Museum, Langham Lane, Langham, CO4 5NW

A look back at orchards

At this darkest time of the year we thought it would be fun to remind ourselves of the Orchards Conference run by the ERO back in the mild month of October. Attendee and FHE Vice Chairman Ken Crowe kindly recorded his thoughts on the day (see below). We hope this will inspire you to support the 2022 forthcoming ERO events programme (details to follow on the ERO website in due course) as well as getting out there to farm shops and local orchards to source some wonderful traditional apples for your Christmas tables – maybe a D’Arcy Spice or perhaps an Egremont Russet.

The Apples and Orchards of Essex: a One-Day conference at ERO, 16 October 2021

A panel of six speakers presented the audience with a fascinating mix of the science and history of apple varieties and orchards, from the early 17th century to the present day. The talks together with the splendid display of many ‘heritage’ apple varieties outside the lecture theatre I’m sure will have encouraged many of the audience to go in search of the community and other orchards instead of relying on the limited range of fruit to be found in supermarkets.

The first of the day’s talks was Paul Read’s ‘What is an Orchard?’

The first thing we learnt was that apples are not ‘native’ at all – they appear to have originated in Central Asia (more of this later!) and then spread through China and Europe. As early as Roman times there was evidence of grafting of apples. Today apple varieties are grafted onto dwarfing rootstocks (M11) at the National Fruit Collection (Brogdale in Kent); the rootstocks were developed at the East Malling research facility, also in Kent.

Fruit trees grafted onto dwarfing rootstocks (M11 and M27) have a life-expectancy of about 20 years, but hard pruning and training facilitates picking, and maintains health and vigour of the trees.

A surprising fact (to this member of the audience, at least) was that fruit trees are almost as good at absorbing carbon as oak trees! I wonder if this will be mentioned in Glasgow!

Peter Laws, ‘Orchard Fruit Varieties: New ways of identification

Peter Laws is a founder member of the ‘Fruit ID project’ (www.fruitid.com/#main). We learnt that it’s no good sowing the pips from your apple and expecting the same variety to emerge. Because pips are the result of cross-pollination, the ten pips from your apple might result in ten new varieties. Also, apples that might look very similar might not be the same variety at all. All very confusing!

Known varieties are grown by grafting on to a rootstock, a method by which genetic identity is preserved. Other (more recently introduced) techniques include micro-propagation, from leaf material, and budding. But then there is the problem of variability in identified varieties: in appearance, taste, fragrance, growth habit of trees, and name(s) by which the ‘variety’ is known. ‘Names’, because there are multiple synonyms for many varieties – 100 for Blenheim Orange alone!

The only reliable method of identifying a variety is by its DNA – in the UK there are 12 markers on the DNA sequence by which a distinct variety is identified.

Anna Baldwin, The Puzzle of Red-Fleshed apples. The Essex Connection.

Red-fleshed apples originated in the China/Siberian border region (Uighur area). In 1894 a bag of pips (of malus Niedzwetzyana – the red-fleshed apple) was carried from Siberia to Kew, via Germany, and then distributed around England. One resulting variety (remember: apples grown from pips will not come true to variety!) was known as ‘Wisley Crab’. The plant was described in Curtis’ Magazine and grown by Canon Ellacombe (the Kew specimen). In 1925 malus ‘Wisley Crab’ was described in the RHS Journal.

E.A. Bowles, a mentor of Canon Ellacombe, bred malus Nied. at Myddelton House. Dick and Helen Robinson grew ‘Wisley Crab’ (m. Nied.) at Hyde Hall. This was identified by DNA, but its profile did not match the original ‘Wisley Crab’. It was also grown at Barnard’s Farm (national collection of Crab Apples).

There are several varieties of red-fleshed apples, each identified by their DNA profiles. The problems and confusion associated with growing apple varieties from pips was amply demonstrated here.

Neil Reeve, Essex Heritage Fruit Trees.

Essex would seem to be the ideal county for growing fruit trees – the climate is relatively dry and sunny, the soils generally fertile and the proximity to markets (especially London) and transport links, excellent. During the last 40 years, however, about 75% of (commercial) orchards in Essex have been lost.

The two most important commercial growers of apples in Essex have been William Seabrook & Sons of Boreham and Wilkins and Sons of Tiptree.

The East of England Apples and Orchards Project (EEAOP www.applesandorchards.org.uk/buy-fruit-trees/essex/) was established to collect and protect varieties. The holding of ‘apple days’ to which the public bring apples for identification, has resulted in the identification and rediscovery of ‘lost’ varieties, which then form part of a propagation programme. The EEAOP provides full identification service and information, training, research and teaching materials. Over 500 schools have been provided with trees to date.

There are 35-40 ‘Essex’ varieties of apples – Essex being the county where those particular varieties were first recorded. The oldest apple recorded was introduced by Dr Harvey, in 1629; among the youngest are ‘Rosy’ (1986) and ‘Easton Countess.’ Picking dates vary from early August (‘George Cave’) to early November (‘Darcy Spice’). The best tasting variety is claimed to be ‘Braintree Seedling’. But, as usual, the biggest problem when it comes to identification of varieties is that of synonyms.

Neil Wiffen, An account of Dwarf Apple Trees planted: a Scheme from Kelvedon, 1831.

Neil’s entertaining talk was based on a detailed hand-written account of the trees planted in the ‘Great Orchard’ by F.U. Pattison in a Kelvedon farm in 1831 (ERO, D/DBm E18). The orchard was adjacent to the farmhouse, for ease of picking, security, and just for the pleasure of the blossom. The account lists the (13) varieties of apples, which Neil researched to establish the date of introduction and origin. The earliest of these, ‘London Pippin’ had Essex as its origin in the 16th century, while most of the others were introduced in the late 17th to late 18th century from elsewhere in England, France and one, possibly, from America.

Neil attempted a reconstruction of the orchard from the description of trees planted between the standards, in ‘long’ rows and ‘short’ rows. It would be fascinating to know if this method was normal practice in orchards at this time.

The apples provided fruit for the table for the whole year, with surplus available for sale at local markets and even further afield, by road (e.g. A12) and later by rail. The availability of accessible markets (centres of population) both near and far was a very important consideration to the success of the orchard as a commercial venture.

Tom Williamson, Orchards East; the Essex Experience

The HLF-funded ‘Orchards East’ project (www.orchardseastforum.org/about) ran from 2017 to 2021, covering seven eastern counties. Tom started with a question: why is the West Country associated with cider production from apples? The answer – malting barley will not grow successfully in the West Country, and so they drink cider instead of beer. However, from the 18th century there was also commercial production of cider in eastern England.

Tom classified orchards into four categories:

Farmhouse orchards, such as that described by Neil in his paper, are characterised by tall trees on vigorous rootstocks, covering up to 1% of the farm acreage, and, like that at Kelvedon, adjacent to the farmhouse. Such orchards are dominated by apples, with pears, plums, cherries and some nuts. Such orchards are multi-use environments, for grazing poultry, bees, hay, fuel.

Commercial Orchards were more likely to be interplanted with fruit such as blackcurrant, gooseberry and sometimes arable crops. These are more intensively managed and sprayed.

Garden orchards, including ‘country house’ orchards, were used as part of a wider garden design; e.g. formally planted orchards would fit in with 17th -18th century style of gardens.

Institutional Orchards attached to workhouses, mental hospitals, etc. because of their therapeutic value (much as access to gardens today).

Today the emphasis is on ‘community’ orchards – those managed for and by the community. There are many of these around the county – a fact that I was unaware of and my mission now is to visit my local community orchards. In fact, on the way home I me up with a member of the audience who was involved with the Eastwood community orchard project. That will be my first port of call!

The important point made by most of today’s speakers was that orchards have been a major part of our ancestors’ lives – and that they were and still are an important part of our shared cultural/landscape history. Well done to ERO for yet another well organised and interesting conference and I look forward to whatever they have organised for 2022!

Ken Crowe

Essex University student internship at ERO

The FHE-have, for several years, supported an internship for an Essex University student at ERO. For 2021 the FHE Committee agreed, exceptionally for this year only, to support two student placements, and Aaron Archer and Adam Campbell-Drew were appointed. Below is an initial report from Aaron on some of his findings.

If you enjoy this, Aaron also has an accompanying post on the ERO Blog (http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/)

Tales from the Parish Chest: migration in early modern north-Essex

by Aaron Archer

During my placement at the Essex Record Office, I have been cataloguing records from various parishes across north-east Essex. In this piece I would like to focus on some of my findings pertaining to two of these parishes: St Osyth and Sible Hedingham.

St Osyth drew my attention for two main reasons. Firstly, I live in St Osyth, therefore there was no shortage of curiosity about the local history of the parish. But secondly, and more importantly, I found myself struck by the range of locations mentioned within the settlement certificates, settlement examinations, and removal orders within its parish chest.

Among these, the relatively local settlements were expected; places such as Colchester, Ipswich, Harwich, Clacton, Wivenhoe… none of these locations struck me as out of the ordinary. However, when I noticed locations such as Boston and Blankney in Lincolnshire, Kirdford in Sussex, West Riding in Yorkshire, and even County Cork, I realised that people were arriving in

St Osyth from all over the British Isles. This itself began to suggest that people in early modern England migrated much greater distances than I had initially expected.

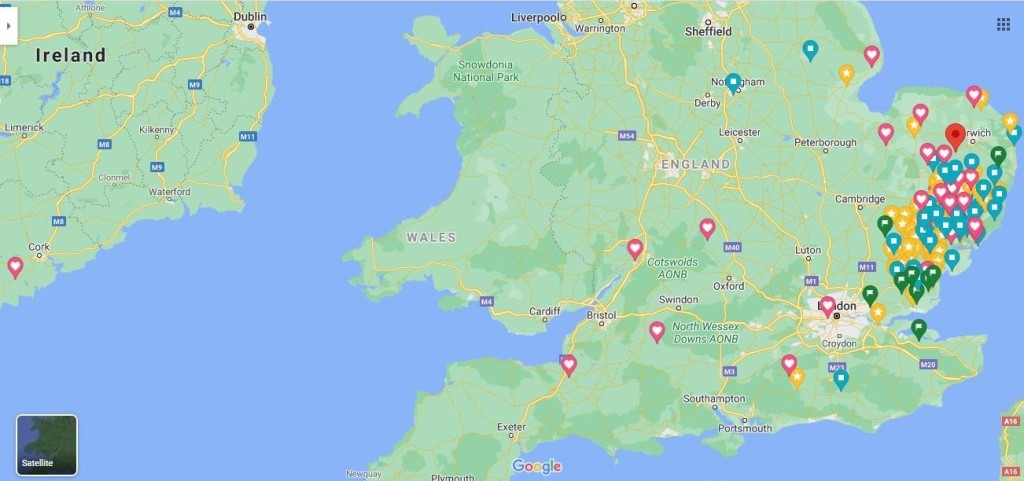

The picture above shows the locations which some of St Osyth’s inhabitants travelled from. The hearts representing birth locations cited in settlement examinations; stars being the origins of settlement certificates; the green flags being locations in which people were removed from back to St Osyth; and the blue squares being locations where people were returned to from St Osyth.

The huge cluster of locations on the east coast are to be expected, since none are considerably far from St Osyth, and many along the coast almost certainly reached the parish by boat. However, some of the other birth locations are a considerable distance away. Moreover, even some of the places that people were removed to, such as Nottingham, are vast distances away in a time where travel by road was limited to walking or to horse and cart.

The real question, though, is why? Why St Osyth of all places? St Osyth itself is not exactly unique. Or, to be frank, particularly interesting. The parish lies four miles from Clacton to its east and twelve miles from Colchester to its west. It was largely rural with little to offer that might draw people in; indeed, many of the people who did end up in St Osyth either worked in husbandry or entered domestic service. These individuals often had not had long term employment, with many stating that their last year’s work was years prior (if they had even ever had long term employment). Unlike its other coastal neighbours, St Osyth did not have a fishing trade, instead this trade was primarily focused on Harwich (sixteen miles away) or Brightlingsea, with its oyster dredging, (about six miles in the other direction). Both locations were frequently mentioned in the apprenticeship indentures of young men born in St Osyth, and then sent to these locations for their tenure.

The positioning of St Osyth may have proved useful as a sort of central hub, with Clacton, Great Bentley and Brightlingsea all within walking distance, and Colchester just a few more miles further beyond that. Essentially this particular route would be a precursor to the B1027 Colchester Road that exists now. This is notwithstanding the potential sea routes available due to being on the coast. Yet still, the range of locations that appear within its settlement documents is nothing short of amazing.

Though, how does St Osyth compare to other parishes in north-east Essex? To consider this, I compared St Osyth to other parishes in north-east Essex, but for this piece I shall focus just on Sible Hedingham – a parish about as far away from St Osyth as I could find!

Sible Hedingham lies only four miles from Halstead, which was a sizeable market town throughout the early modern period. As such, one can understand that there may have been some allure to the parish, due to its proximity to Halstead.

Looking at the map here, there are some similar trends. Again, there is the expected cluster in the south-east around the parish, but also two anomalies – Perth and Dublin. Unlike the examples in the St Osyth records, both have detailed settlement examinations associated with them, describing journeys across the British Isles in search of work before finding their way to Sible Hedingham.

According to his settlement examination (D/P 93/13/4/10), the individual from Dublin, Thomas Buttler, was born in Castle Dermott, and was bound apprentice to a butcher named Richard Pearson in ‘Kilabien’ in Queen’s County. He then travelled to Dublin for work for two and a half years before moving to England and working as a labourer in London on several occasions before he eventually ended up in Sible Hedingham.

It is a similar story in the settlement examination for James Hutchson of Perth (D/P 93/13/4/13). He lived in Forgen, Perthshire in Scotland until the age of 18. He was bound apprentice as a tailor for three years, and then worked for his master for a further year. He came to England in 1733 but he does not discuss any notable work between then and his examination in 1742.

These individuals covered huge distances to faraway towns, and one imagines that they were never entirely aware of what was waiting for them at the other end of their journey. Yet, it is apparent with both cases, these journeys were necessary in search of work – particularly searching for long-term employment.

So, I expect I am now being asked “what does this all mean?” and “where am I going with this?”.

It is too early to make any conclusions, and a blog post is too limited to make any strong assertions anyway. However, this evidence certainly supports the recent research stating that migration was more prevalent and spanned greater distances than was once thought.

Whilst many who were caught travelling across the country were accused of vagrancy, it is apparent that at least some (if not many) of these individuals were travelling in search of more long-term employment, rather than the weekly or monthly labour they often found. In doing so, they travelled parish to parish (usually either coastal or parishes on routes to larger towns), performing short-term labour and eventually would find themselves brought in for a settlement examination by the churchwardens and the overseers of the poor – especially if they were caught seeking poor relief.

As Fumerton has suggested in her book, Unsettled, despite the state desire for an idealised settled population of workers in service to their masters, we instead find a reality of an early modern England replete with a mobile population of often dispossessed and alienated individuals forced to roam the country in search of work.

Clark, P., and Souden, D. (eds), Migration and Society in early modern England, (London: Routledge, 1988).

Fumerton, P., Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England, (London: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Notice of FHE 2021 AGM

The Sixty Eighth Annual General Meeting will be held by e-mail on 24 July 2021 due to the

COVID-19 public health emergency

FHE Notice of Virtual AGM 24 July 2021

FHE AGM Acceptance form 24 July 2021

FHE AGM 2021 Item 1 minutes 2020 AGM

FHE AGM 2021 Item 2 Chairman’s Report

Item 4 FHE 2020-21 accounts page 1

Item 4 FHE 2020-21 accounts page 2

Vaccination in the 18th century

After two months, millions of the most vulnerable of the population have been and continue to be vaccinated against Covid-19. In addition to hospitals and GP surgeries round the county, other venues such as the Harlow Leisurezone, the Cliffs Pavilion in Southend, Chelmsford City Racecourse and Colchester Community Stadium are being used.

The first vaccine dates from 1796 when Dr Edward Jenner from Gloucestershire vaccinated his gardener’s son James Phipps with cowpox, a milder form of the smallpox virus. Vaccination in turn derived from the practice of inoculation, which used the live smallpox virus and was widely used in Asia and Africa. Inoculation came to England after Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul, saw its use there. She had her son inoculated in Turkey and after her return her daughter was inoculated in London in 1721. The practice soon spread as a means of combating the frequent outbreaks of the disease in the 18th century.

Among the leading inoculators of the 18th century was Daniel Sutton, originally from Suffolk, who set up his practice in Ingatestone in 1763. Inoculation was controversial, as it was often blamed for outbreaks of the disease. Frequent complaints and even prosecution against Sutton, encouraged the Revd. Robert Houlton, described as the officiating clergyman at Mr Sutton’s, to preach on 12 October 1766 at Ingatestone The Practice of Inoculation Justified (LIB/SER/8/26 and 26/10). Daniel Sutton inoculated thousands of people and made enough money to acquire property in Ingatestone and Eastwood (National Archives PROB 11/1614).

The devastation that smallpox caused led many parish vestries to pay for their parishioners to be inoculated and later vaccinated against smallpox. Rainham overseers’ accounts include a payment for inoculation in 1770 (D/P 202/12/1/36), the Theydon Garnon parish register (D/P 152/1/5) records the inoculation of paupers in 1781, 1787 and 1797. In 1810 and 1818 the parish of Kirby-le-Soken paid for parishioners to be vaccinated and the parish of Saffron Walden between 1820 and 1831 paid 1s. 6d. per head to various doctors to vaccinate hundreds of parishioners (D/B 2/PAR9/27).

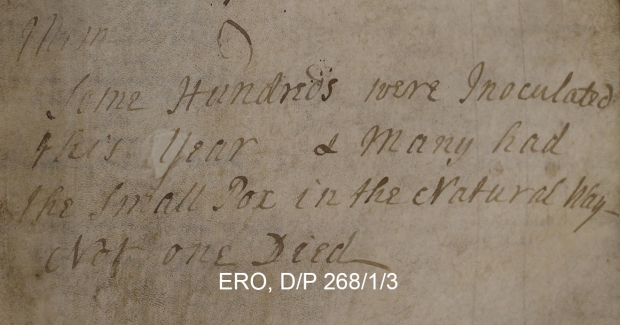

Since the 18th century, many vaccinations have been developed against many diseases and smallpox itself has been eradicated from the world. Vaccination brings hope today as it did in the 18th century. The Bocking parish register recorded the burials for 1796 (above) and then noted Some Hundreds were Inoculated this year & many had the Small Pox in the Natural Way Not one Died.

Katharine Schofield, Archivist, ERO

To find out more about the history of vaccination and inoculation you might like Essex Record Office publication 95, The Speckled Monster by John Smith. This is available from the Searchroom for £14.95. For further details please email: ero.searchroom@essex.goc.uk.

Responses to pandemic: examples from seventeenth century Essex

Essex Record Office archivist Katharine Schofield looks back at how Essex responded to pandemics in the past – it all seems very familiar.

As we struggle in a world transformed by the coronavirus global pandemic, it is interesting to look back on events of more than 350 years ago to see how the county coped with a major epidemic, in this case, of bubonic plague in 1665.

In the 17th century nobody knew what caused plague or how to treat it. There was an understanding that it was spread by contact, but there was no knowledge of how this happened until the 19th century. Today, we look to central government, as well as local authorities, to provide the essential services to protect us. By 1665 there was an established procedure to deal with epidemics in parishes and towns. There was, however, little in co-ordination beyond the individual places where the plague struck.

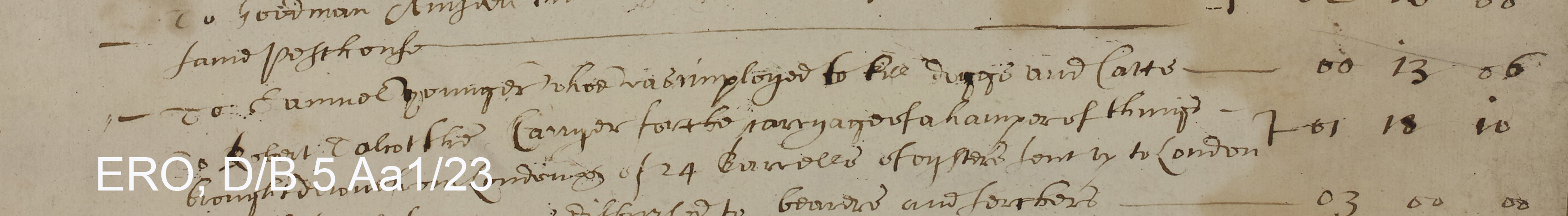

It was widely believed that miasma (bad smells) were to blame for the spread of plague. It was of course also well-established that you could catch the plague from another infected person. Stray cats and dogs were also blamed and the chamberlain’s roll for the borough of Colchester (D/B 5 Aa1/23) records payments of 13s. 6d. to Samuel Younger whoe was imployed to kill dogs and catts and a further 18s. to the dogg killer.

To Samuel Younger, dog and cat killer 13s. 6d. (D/B 5 Aa1/23, Colchester Borough, Chamberlains’ Accounts, 1665)

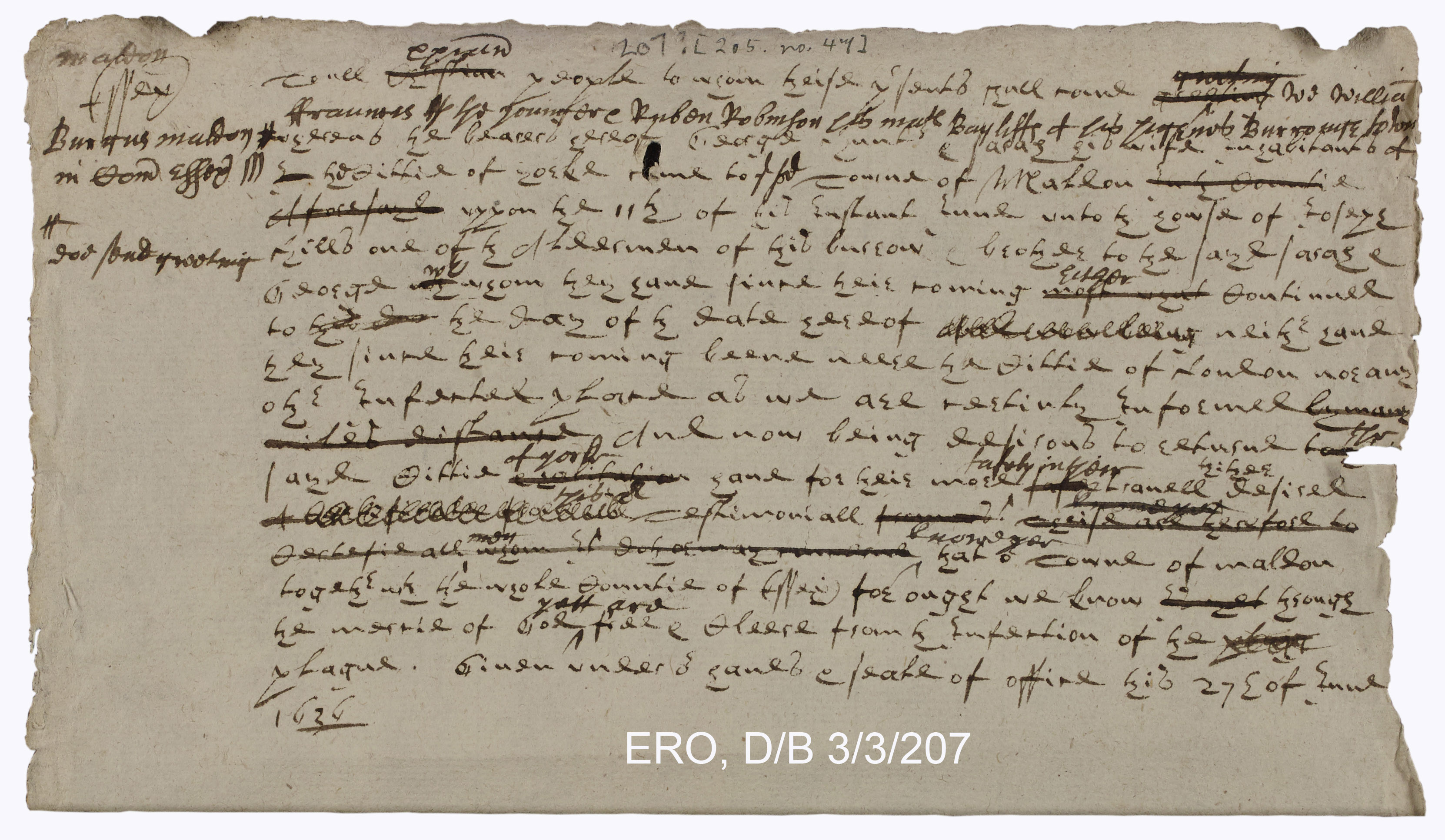

The first line of defence was to try to stop people travelling and spreading the infection. On 27 June 1636 the bailiffs of the borough of Maldon provided a certificate (D/B 3/3/207) to George and Sarah Hunt of York who had arrived in the town on 11 June to stay with Sarah’s brother Alderman Joseph Hills. The certificate stated that they had not left the Borough neither have they since their coming beene neere the Cittie of London nor any other infected place and that they asked for this Testimoniall for their more safety in their travel , concluding with the statement that Maldon and the whole county of Essex for ought we know, through the mercie of God, yet are free and cleere from the Infection of the plague.

Certificate issued to George and Sarah Hunt of York. (D/B 3/3/207, Maldon Borough, Court Papers, 1636)

The use of certificates was not always a complete success. At the Michaelmas Quarter Sessions of 1665 (Q/SR 406/104) a case was presented on the evidence of John Branch, a grocer from Wivenhoe. He had a warrant to stop people coming to Wivenhoe from London not having lawful certificates and that any people without certificates should be stopped from landing. Hewes, the master of a packet boat moored at Wivenhoe Quay had many passengers from London and Branch required that passengers should not come ashore without a certificate showing that they were infection free, but they refused to obey and pressed by violence to come on shore. Branch asked two passers-by, Thomas Collin and Thomas Clarke to assist him. Instead of assisting him, Clarke bid a turd in [Branch’s] teeth and Collin took his boat to help the passengers ashore.

Plague spread out to Essex from London. In mid-July Samuel Pepys visited Dagenham and recorded in his diary that all these great people here are afeared of London, being doubtful of anything that comes from thence or that hath lately been there. The epidemic first reached Chelmsford and Colchester the following month. Both Colchester and Harwich traded directly with Rotterdam, where plague had raged since the previous year and this perhaps explains why Colchester was to suffer more.

By the mid-16th century it was customary to isolate the infected in their own homes which would be marked with a cross, or in a pest house, if available. Colchester’s assembly book for May 1666 (D/B 5 Gb4 f.319-320) records payments to a Halloway of the parish of St. Giles who was paid £4 9s. for making ye crosses on ye doors of infected houses and a further £4 1s. for making red crosses. In Chelmsford 1s. 4d. was paid to Blakeley for stapleing up severall dores and 10 stapells.

We have seen how quickly the Nightingale Hospitals have been built in different locations round the country and in 1665 Colchester built a pesthouse in the parish of St. Mary-at-the-Walls to accommodate plague victims who could not ‘self-isolate’ at home. The account roll of Thomas Merridale, chamberlain for the borough (D/B 5 Aa1/23) includes payments of 7s. to Goodman Johnson for glazing and £2 10s. to Goodman Amsden for masonry work. The scale of the epidemic in Colchester was such that one pest house was insufficient and another was built in Mile End at a cost of between £86 and £92, roughly the equivalent of wages for three and a half years for a skilled craftsman. In Chelmsford an isolated house was purchased to house the sick at Stump Cross (today the location of the Wood Street roundabout) with 1s. 2d. paid for making cleare a house at Stumpe Crosse.

We are of course lucky today to have the National Health Service to care for the sick and for income support from central government for people and businesses. We have also witnessed fund-raising efforts for NHS and other charities. In 1665 there was no support from central government for people unable to work through sickness and individual parishes and towns made their own provision for plague victims. They were soon overwhelmed by demand.

Such was the level of distress in Colchester that money was raised to relieve the suffering of the poor. At Earls Colne, the Revd. Ralph Josselin recorded on 4 October 1665 Wee remembered poore Colchester in our collection, neare 30s. and sent them formerly £4. In 1665 Essex was part of the Diocese of London and the Borough assembly book for 9 October 1665 (D/B 5 Gb4 f.315) records The distribucion of the £16 7s. of the Charitable monys collected in the Country upon Fast days towards the releefe of the infected poore granted to this Towne by the Bishop of London. Nine days later a further £30 was distributed.

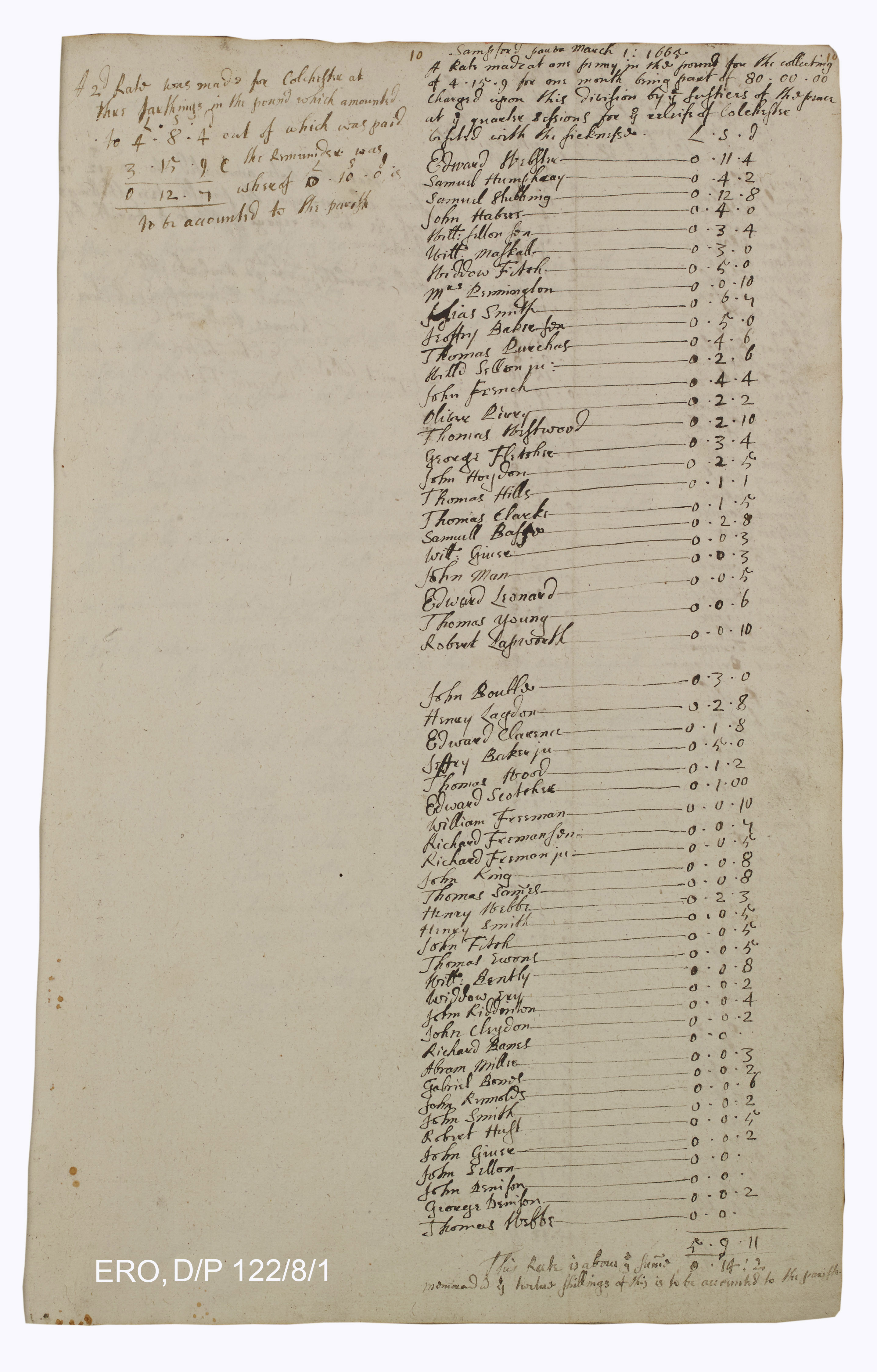

Money was also raised for Colchester throughout Essex by order of Quarter Sessions, administratively the predecessor of the County Council. This started with parishes within 5 miles of the town and gradually spread further afield. On 11 November 1665 the assembly book records that Alderman Moore received fower score and ten pounds of the hundred and Eight pounds taxed upon the Country five miles distant from this Towne for one Month last past. As need grew, five miles was later extended to the Hundreds of Lexden, Dunmow and Hinckford, with churchwardens’ accounts in Little Sampford and Great Bromley recording the money raised. Chelmsford’s plague outbreak had started at the same time as Colchester and by January 1666 distress had risen so that Quarter Sessions agreed a similar rate to be paid by the hundreds of Chelmsford, Rochford and Dengie for the relief of the town.

By May 1666 weekly collections were being made in London parishes for Colchester (£2,700 were raised by these means) and the assembly book on 13 May records a collection made in all London churches.

On occasion money was given by individuals for the use or releefe of the afflicted or infected poore of Colchester (D/B 5 Gb4 f.324-325). On 6 June 1666 the borough received £57 5s. 5d. collected in the city of Exeter, in May £20 was given by a London merchant unwilling to discover his name. Sometimes the gifts were made by people with local connections, Sir Harbottle Grimston, Master of the Rolls gave £20 for the infected poore and in July £5 was given by Thomas Clarke of Ipswich, described as the son of a former sergeant at mace of Colchester. In Braintree, another badly affected town, Charles, Earl of Warwick gave 2 bullocks a week and £12 to maintain a doctor and apothecary and his servants gave £20, while Lord Maynard gave 30 sheep and £10 and the inhabitants of Coggeshall £33.

Sir Harbottle Grimston’s gift of £20. (D/B 5 Gb4, Colchester Borough, Assembly Book, 1665)

In total approximately around £5,000 was raised and spent in Colchester, the equivalent of more than 195 years of the wages of a skilled craftsman. Costs were estimated at the height of the epidemic to be in the region of £500 a month. In Chelmsford in September 1665 the parish spent £27, in October it peaked at £73 (more than three years’ wages of a skilled craftsman). A total of £686 (around 27 years of wages) was spent before the plague ended.

Rate collected in Little Sampford for the relief of Colchester. (D/P 122/8/1, Lt Sampford St Mary, Parish Book, 1666)

We have become accustomed in recent weeks to ‘social distancing’ when outside. In Colchester in 1665 the searchers, who ascertained the cause of death of plague victims, and bearers, who carried the bodies to their burial swore an oath that Yee shall live together where you shall be appointed and not walke abroad more than necessity requires and that onely in the execution of your office of Searchers [or Bearers]. Yee shall decline, and absent yourselves from your familys, and allwaies avoide the societye of people and in your walke shall keepe as far distant from Men as may be allways carrying in your hands a white wand by which the people may know you and shunn and avoide you (D/B 5 R1 f. 217).

Colchester appointed its first bearers James Barton and John Cooke on 16 August 1665. In October the assembly book records the name of the two surgeons, Mr Raer (Chirurgeon and Pestmaster) and Mr Hendrik (a Dutch Chirurgeon) and the searcher Mr Streete. In Chelmsford, the overseers’ accounts (D/P 94/12/2) convey something of the stresses that the disease brought. John Green was appointed to manage the situation and he recorded payments made to him, including £5 promised me for my extraordinary care and trouble in looking after ye infected families in Moulsham and later 15s. for fire and candle and beer spended at my house those nights the corps were buryd. The accounts include payments to bearers Daniel Stevens and Michael Hatton and 3s. to Widow Roberts and Widow Jurmay for laying forth 3 Corps and watching one night.

Payments £5 and 15 shillings paid to John Green. (D/P 94/12/2, Chelmsford St Mary, Overseers’ accounts, 1665)

Today, we are grateful to the dedication of all the key workers who are keeping the country working, feeding the nation and of course, to the NHS staff on the front line. Their dedication reflects that of people in 1665-1666 who battled the plague and tried to keep their communities safe from disease.

Katharine Schofield

1735 estate map purchase

Recently the Friends of Historic Essex have generously funded the purchase of a colourful plan of a modest 27 acre property called Great Childs, belonging to the Rev. Thomas Forbes, rector of Little Leighs (ERO, D/DU 3263). The cartouche names the surveyor as John Waite, and states that the estate straddled the parish boundary between Little Leighs and Much (Great) Waltham. The plan itself shows that it lay south of the road to Littley Green, making it possible to accurately locate the site. (TL 703 174)

Little is known for about Forbes before his arrival at Little Leighs. He probably obtained his MA degree at Aberdeen in June 1694, was ordained deacon the same day by the bishop of London and appointed schoolmaster at Monoux’s school, Walthamstow a fortnight later. He was ordained priest in June 1695. We do know that he was instituted rector of Little Leighs in August 1701, and that he died and was buried there nearly half a century later in January 1750.

The house belonging to Forbes’s estate lay immediately to the north of the Littley Green road, just inside the parish boundary of Great Waltham. Immediately to its north and east the plan clearly shows the pale of Leez park, together with a narrow strip of woodland, marked ‘The Old Wilderness’. This is of great interest and raises a number of questions.

Extract from the map showing the Park pale and ‘The old Wilderness’.

Nothing is known about the formal gardens at Leez. The priory had been acquired at the dissolution by that unscrupulous parvenue, Richard Rich (1500-1568). He demolished most of the monastic fabric to build a grand mansion round two courtyards and, at the same time, he acquired Littley Park which lay to the south. This medieval deer park provided Rich with an instant cachet of respectable ancestry, as well as an opportunity to make a new, more convenient and much grander access to his mansion from the south. The Old Wilderness, which is shown on Forbes’s estate plan, is just inside the pale on the eastern edge of Littley Park.

To those of puritan conviction, the most important resident of Leez was Mary Rich, countess of Warwick (1625-1678), the wife of the fourth earl, one of Richard Rich’s descendants. Her diary reveals a daily cycle of prayer and meditation, with many references to ‘the wilderness’ to which she retreated to escape from the distractions of domestic life at Leez. On receiving news of the Great Fire of London in September 1666, for example, she ‘went out into the wilderness to meditate, and to endeavour by meditation to put my soul into their soul’s stead, that were spoiled by all, and had not a house to lie in’.

It is generally accepted that Mary Rich’s wilderness was not in Littley Park but in the old monastic park, immediately to the north of the mansion, accessed by crossing a bridge over the river Ter. This appears to be confirmed by first edition 6” OS map of 1875 which shows a

square enclosure in this position, marked ‘The Wilderness’. What then was ‘The Old Wilderness’ shown on Forbes’s plan?

Due to its relatively modest status, it is most unlikely that Littley Park would have had a wilderness before its acquisition by Rich in the 1530s. However ‘The Old Wilderness’ is almost a kilometre from the mansion of Leez, seemingly an unlikely place to construct one. As already mentioned, nothing is known about the formal gardens that Rich planted round his new mansion, though it is tempting to imagine that there was once an extensive formal landscape extending from the house to the later site of Forbes’s dwelling, of which ‘The Old Wilderness’ was the only remaining fragment by 1735. Both the mansion and its surrounding landscape would have come dramatically into view on reaching the summit at the northern end of the causewayed drive that Rich had constructed through Littley Park. It would have provided a setting worthy for a self-made Tudor billionaire (though it must be emphasized that there is no archive evidence to support this speculation). After a long decline, the majority of the mansion was demolished in 1753, though most of Littley park (including the area occupied by the Old Wilderness) had remained paled and stocked with deer until that date. Subsequently it was disparked, and divided up into named fields. It has been farmed for at least a century and a half, and any trace of the formal garden that might once have existed would have been destroyed.

Forbes died in 1750 and left his property of 27 acres and 35 perches (which he called Good Childs) to his ‘legitimate or illegitimate’ grandson. Most of his fields were amalgamated in the twentieth century to form a large orchard, but the footpath which divided his property is still a right of way, and still follows the parish boundary between Little Leighs and Great Waltham.

Michael Leach

Sources:

Anon (ed) Memoir of Lady Warwick & her Diary (London, 1847).

Chancellor, F. ‘St John’s church, Little Leighs’ in Essex Review, iv (1895), p.196.

Clark, R, ‘Wildernesses and Shrubberies’ in Journal of Jane Austen Society vol 36,

no. 1 (2015).

Fell Smith, C, Mary Rich, Countess of Warwick 1625-1678 (London, 1901).

Hunter, J. ‘Littley Park, Great Waltham’ in EAT, xxv, 3rd series (1994), pp.119-24.

Leach, M, Leez Priory entry in Chelmsford Inventory

(unpublished Essex Gardens Trust MS, 2010).

Thomas Forbes’s estate map, ERO, D/DU 3263, 1735.

Will of Thomas Forbes, ERO D/ABW 96/3/7, 1750.

Sketch plan of Littley Park ERO D/DGh E14, 1753 (or later).

Church of England Clergy database, accessed 0/03/2020 .

Record rescue: photographs of First World War Clacton nurses purchased for Essex Record Office

Hannah Salisbury, Essex Record Office

From time to time we see things come up for sale at auctions (and even on ebay) which have a place in the Essex Record Office’s (ERO) collection of records of Essex people and places. The ERO, however, has only a very small budget to purchase documents. This makes us even more especially grateful for the support of the Friends of Historic Essex who, where they can, purchase documents for preservation at the ERO, so they can be discovered and used by researchers.

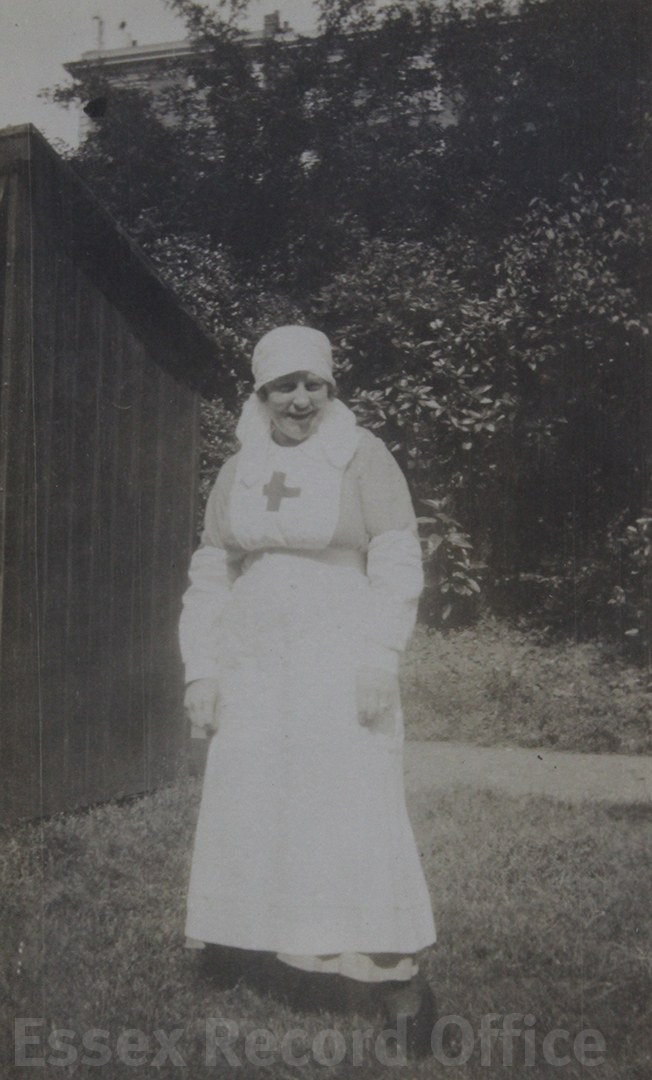

One such recent purchase made by FHE is this set of 14 photographs of nurses at a Clacton hospital. They have been removed from an album, and therefore potentially from precious context which could have given us valuable information about their owner and the people in the pictures. We have done our best, however, to work out where the photos were taken, and find out about the lives of the women they show.

11 of these photographs date from the First World War, while 3 look to date from the Second World War. There was little written information on the photographs, but we have managed to establish that they relate to the Middlesex Hospital in Clacton, a convalescent hospital which was converted to military use immediately after the declaration of war. During the war, the hospital treated a total of 9,242 wounded and sick soldiers, including 4,622 cases of gunshot wounds, 415 cases of trench foot, and 110 cases of shell shock.

We are able to discover such details because in the immediate post-war years the two surgeons who ran the hospital, Comyns Berkeley and Victor Bonney, wrote a book about the hospital’s wartime service, The Annals of The Middlesex Hospital at Clacton-on-Sea during the Great War, 1914-1919. A copy of this is handily available in the ERO Library, and has been an invaluable aid in our sleuthing.

Two of the photographs have the name ‘Patterson’ written on the back – perhaps the owner of at least those photographs at some point. The book includes a list of staff at the hospital, which names a Miss T.G.A. Patterson as one of the nurses.

This photograph is marked on the back as being a visit by Princess Alice to the hospital in 1917. It was through comparing the building in the background of this picture with images of the Middlesex Hospital that we have been able to confirm which hospital the pictures relate to. Princess Alice is the lady in civilian clothing in the second row back, second from the left. Her husband is next to her, and her two children in front. Through comparing this image with others in the Annals, it has been possible to identify the lady in the front row in the matron’s uniform is Georgiana Morgan.

Miss Morgan had been Matron of the Convalescent Home before it was converted into a War Hospital. Not only was she a trained, experienced nurse, but she had also nursed for the military before, in South Africa during the Boer War. In the Annals, the authors tell us that Miss Morgan deserved ‘special mention’:

‘Her powers of organisation and management had full scope… On Miss Morgan fell most of the responsibility for the management of the men and the orderlies, and all the responsibility for the nursing of the men and the management of the nurses and domestic staff, together with the catering and the outfitting of the soldiers. In addition, she was primarily concerned in the arrangements for the transfer of the men to the auxiliary hospitals. Miss Morgan was of great help to us not only in the wards and as our chief assistant at most of the operations, but also in the important matter of splint-making, for which she exhibited a remarkable natural capacity. The first-class Royal Red Cross, which she received from the King, was most thoroughly deserved.

She could turn her hand to anything! On one occasion a patient came down to the theatre for operation and was comfortably settled on the oeprating table. There was a wait, as the surgeon had been detained in one of the wards. Suddenly the matron said: “Your hair is dreadfully long; it wants cutting.” The man consented without enthusiasm, climbed down from the table, and, taking his place on a chair outside, the scissors were vigorously applied. However, she had only got half-way through when the surgeon appeared, and so the man had perforce to be satisfied with the remark that half a cut was better than no cut at all.’

The Annals of The Middlesex Hospital at Clacton-on-Sea during the Great War, 1914-1919, pp.23-24

In 1917 Miss Morgan was awarded the Royal Red Cross, a medal given for exceptional services to military nursing.

Judging by their uniforms, most of the photographs seem to be of Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) (the information on Sue Light’s Scarlet Finders website about identifying uniform has been invaluable).

These photographs seem to all show VADs in the first year of the war. VADs wore mid-blue dresses and white aprons, sometimes with a red cross. Until summer 1915 they wore caps like the ones in these pictures, while professional trained nurses wore a veil style headdress.

After summer 1915, the VAD headdress changed to the handkerchief style cap tied at the nape of the neck, as modelled by the lady in this photograph.

In autumn 1917 stripes were introduced for VADs to wear on their sleeves. White stripes denoted length of service working for the Joint War Committee, so it looks like the VAD in this photograph had 2 years’ service at the time the picture was taken.

The VADs were volunteers, with no experience of hospital work. Relations between trained nurses were not always easy, but ultimately VADs proved indispensable to the running of a hospital in wartime.

‘All the V.A.D’s, including those who were on the staff, as well as those who came to us for training before being drafted to Red Cross hospitals, worked just as hard as the nurses. They were very popular, not only because they were good at their job, but also because they did as they were told without any grousing or superior airs. Moreover, they were really most useful in spite of the welcome one of the first batch got, “We may be of use to you, but you will be of no use to us,” which welcome was handed down to succeeding generations of V.A.D.’s by their colleagues, as part of the ceremony of their initiation.’

The Annals of The Middlesex Hospital at Clacton-on-Sea during the Great War, 1914-1919, p.29

According to the caption on the back this photo shows ‘Someone who appears to like work!’ Judging by her veil headdress this lady is a trained nurse, at work up on one of the first floor verandahs on the front of the hospital.

Of the nurses, the Annals has to say:

‘…the work that they [the nurses] did was most excellent. For the first few days following the arrival of a convoy they had a terribly hard time, most of them working all through the night and continuing for the whole of the next day, so that, on many occasions, they were on duty for thirty hours or more, with practically no rest… The nurses were all popular with the wounded men, and we never heard a single complaint; on the contrary, a large number of relatives who visited their sons expressed to us on many occasions their great gratitude for all the nurses had done.’

The Annals of The Middlesex Hospital at Clacton-on-Sea during the Great War, 1914-1919, pp.25

The nurses did sometimes get to enjoy some time off, and sea bathing on the beach at Clacton was one of their favourite ways to enjoy themselves:

‘The work of the nursing staff was arduous, especially when we had a “full house”, but, at intervals, they did not have such a bad time… Bathing, lunch on the beach, and occasional pleasant picnics in the country around occupied off-duty hours in the summer time.

Bathing was very popular, and the day nurses used to get up at 5 a.m. to bathe before going on duty. In spite of seaweed and occasional shoal of jelly fish, several learnt to swim. The preparations for bathing were, however, trying, the beach being too far away, even if the authorities had been complacent, to go down in dressing gowns, whilst there were no rocks behind which a bathing costume could be discreetly donned. This difficulty was partly surmounted by the purchase of a tent and by bathing in detachments. The tent was a flimsy affair, and of the variety known as bell. It would accommodate three nurses at a time if two undressed whilst the third held the pole. The change of garments had to be effected standing up, and the physique of the occupants had to be of the average, since, so we are informed, one of the necessary movements entails a certain amount of stooping. On occasions, therefore, only two were allowed inside the tent. It happened one day that a proper supervision in this respect had not been made, with the result that two of rather more generous proportions than average entered the tent with the pole holder. The undressing had to be done in regular drill fashion to keep the tent more steady, similar articles having to be shed at the same time. When, in due course, the stooping movement came, it was too much for the guy-ropes and over went the whole show, which would have been all very well for a revue, but it was most fortunate that the Clacton police were not on point duty at this spot; otherwise there might have been lots of trouble, as the Town Council is one of the most particular in the kingdom as regards the amenities of the foreshore.’

The Annals of The Middlesex Hospital at Clacton-on-Sea during the Great War, 1914-1919, pp.25-26

To come round full circle, we finish with another photograph marked as being taken on the day that Princess Alice visited in 1917, which shows a VAD on the left of the back row, and six women in the uniform of trained nurses.

The photographs now have a permanent home at ERO and will be available to present and future generations of researchers.

For anyone interested in the history of First World War nursing, The Annals of the Middlesex Hospital is definitely a recommended read – both informative and full of character. It can be found in the local history section of the ERO library under E/CLAC.

If you would like to help the Friends to buy documents for the ERO collection when they come up for sale, you can become a member , sign up to Give as You Live to raise money when you shop online (at no cost to you!), or make a donation.